The rock church of Santa Lucia alle Malve is the first female monastic settlement of the Benedictine Order, dating back to the eighth century, and the most important in the history of the city of Matera.

A community that through its three successive monastic seats of Santa Lucia alle Malve, Santa Lucia alla Civita and Santa Lucia al Piano has been an integral part of the life of Matera following its historical-urban development over the course of a millennium.

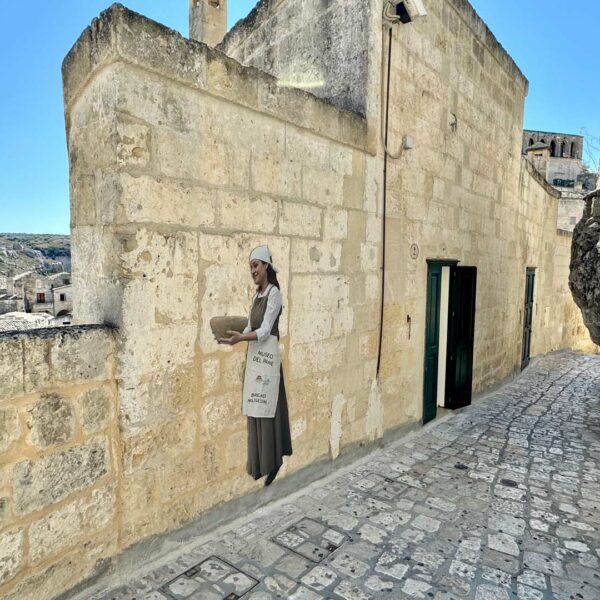

The external front of the former monastic complex develops along the rocky wall with a series of entrances that lead into as many internal cavities. The rooms of the Community are identified by its presence, sculpted in relief at the top, by the symbolism of the martyrdom of Saint Lucia: the chalice with the two eyes of the Saint.

The entrance to the church, on the right of the complex, is highlighted by squared blocks of tuff that draw the line ending with a pointed arch on the bottom of which, within a lunette, is the liturgical symbol of the Saint.

Santa Lucia alle Malve is a large rock church that develops in three distinct naves which, despite having undergone heavy upheavals, after being abandoned by the monastic community, has left many of those marks to allow, with a pinch of imagination , to reconstruct the planimetric and architectural development.

Of the three naves that articulate the internal space, the one on the right, in which it is the current entrance, has always remained open for worship, so much so that even today on the day of Saint Lucia, 13 December, a solemn mass is held here, while the other two naves were transformed into homes and warehouses until the 1950s: a transformation that involved almost all the rock churches present in the two districts of the Sassi, as they were replaced, liturgically, with buildings of worship erected in the new district of the Piano . These rupestrian churches, desecrating, were transformed into homes, service rooms, warehouses, etc. with a process that began in the eighteenth century and went on until the dawn of the twentieth century

Originally, the central nave must have had individual liturgical spaces with an ascending progression from the level of the entrance door, up to the apse where the altar was located.

The presbytery, of all three naves, that is the part reserved only for priests, was enclosed by a series of columns, currently cut off, which descended from the vault offering a touch of high suggestion increased by the mobility of the light emitted at the time. from oil lamps.

The central nave was enriched by an iconostasis, that is the architectural element belonging to the liturgical spaces of the Greek Orthodox cult, which forms a divider between the nave of the church (classroom) and the presbytery part, embellished by the thin columns descending from the vault and by a base enriched by a series of frescoes that are currently found, sawn into squared blocks that make up a grotesque puzzle, in the structure of a flint located in the left aisle. A massacre that occurred during the transformation of part of the church into a home.

Noteworthy, in the flat vault, are the lenticular cavities that enrich the prebiterial area: they are symbolic domes highlighted, in their size, by a series of concentric circles that give a sense of depth.

An introductory speech is necessary to explain the presence of very ancient frescoes, some even of a millennium, so wonderfully preserved: they perfectly preserve their colors and their subjects only if executed with a precise technique, well known in the Matera area by the many active fresco masters. over the centuries.

This ancient artistic expression involved the drafting of a very wet layer of plaster on which a model in cardboard or other materials was placed with the shape of the subject to be finely pitted. It was then dabbed with a small patch soaked in coal dust, thus leaving a trace on the light plaster. This explains the reason why in some cases, and often in the same church, there are two frescoes perhaps in different colors but with the same shape, often even in positive and negative, as the same cardboard was used as a template but perhaps turned in the contrary.

Subsequently, the fresco was definitively outlined and colored, using colors obtained by mixing lime, tuff powder, sometimes organic substances with vegetable pigments derived from flowers and plants and with colored powders derived from the shredding of particular minerals and earth. All this had to happen, however, as long as the substrate was still damp, in fact by drying it fixed the color practically indelibly, as we can still observe today.